You are in the Champions League Final.

The match after regular playtime is a draw, and it all comes down to penalty shooting.

You get ready as Lionel Messi approaches the ball…

Now, what do you do?

Do you jump left, right, or stay in the center?

This is the exact question a team of researchers led by sports psychologist Michael Bar-Eli wanted to find out.

They collected video footage of 286 penalty kicks from actual games in top male soccer leagues.

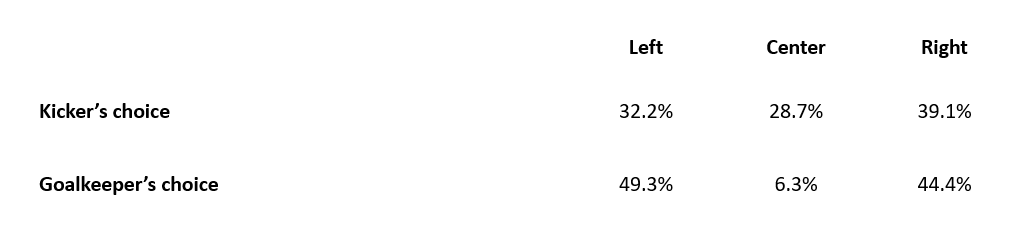

First, they wanted to find out where the soccer players would kick the ball:

Was it to the left, to the center or to the right?

What they found was that on average, a kicker would choose to shoot to the left side 32.2% of the time.

To the right side 39.1% of the time.

And to the center 28.7% of the time.

Here is what they found:

Statistically, 49.3% of the time, a goalkeeper would jump left.

44.4% of the time to the right.

And 6.3% of the time he would remain in the center.

What do you think a goalie could do to increase his chances of stopping a penalty?

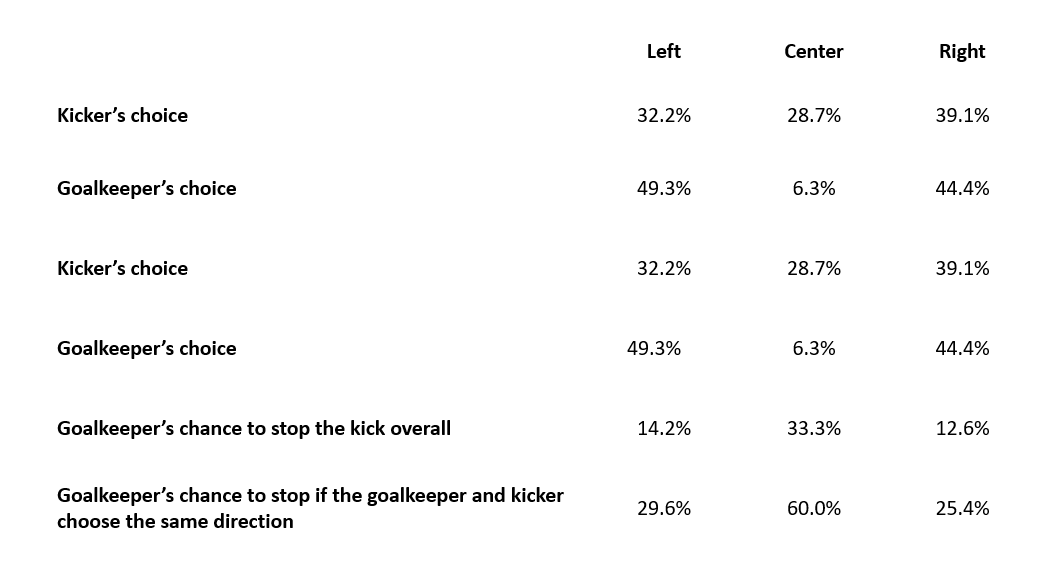

This is exactly the question the researchers wanted to find out and analysed the numbers further.

They found a goalkeeper would stop a ball in 14.2% of the time if he jumped to the left.

In 12.6% of the time if the goalkeeper jumped to the right.

And 33.3% if the goalkeeper stayed close to the center.

In other words, staying stuck to the middle would increase their chances significantly to stop a penalty kick.

In fact, if the goalkeeper and the kicker would choose the same direction, the goalies success rate would increase to 60% when staying in the center ( compared to 29.6% when he jumped to the left side.25.4% when the goalie jumped to the right side)!

PENALTY KICK OUTCOMES

While a football player shoots the ball 28.7% of the time towards the central third of the goal, the goalkeeper actually only chooses to cover the center in 6.3% of cases.

This is surprising as a goalkeepers chance to stop the ball when staying in the center is 33.3%, compared to 14.2% when jumping to the left side and 12.6% when jumping to the right side.

This stat is even more confusing if we consider that a goalkeeper's chance of stopping a kick is 60% when his choice matches the direction of the kick, compared to only 25.4 percent when the kick is directed to the right and 29.6% when the kick is directed to the left.

In other words, the chances of stopping a kick are much higher when a goalkeeper remains in the center.

Nevertheless, in 93.7% of the time, they preferred to jump to one of the sides.

How come?

From a logical point of view, this makes no sense.

We would think that a goalie’s behavior would optimize his chances of stopping a ball.

So why would a goalie not maximize his chances of stopping the ball and stay in the center more often than jumping to one side or the other?

In a 2008 New York Times Magazine article, Michael Bar- Eli suggested that this non-optimal behavior by goalkeepers could be explained by the fact that a goalie would feel worse if he conceded a goal due to not doing much, rather than jumping to one side or another.

These feelings relate to the fact that a goalie can’t fully control whether he stops a penalty kick or not- in fact, more often than not he will fail to stop a penalty kick.

So he starts worrying about how fans, the coach, the manager, sponsors and the media will judge him.

And here is the thing:

People favor the heroic jump to the corners to a goalie who concedes a goal while remaining stuck to the centerline.

Or said differently:

The reason only 6% of the time a goalie remains in the center of his goal during a penalty shooting, even though he would have a 33% chance of stopping the ball and 60% of the kicks directed towards the middle is because he fears to embarrass himself and be considered lazy!

So how does this relate to you, as a young tennis player?

Did it ever happen to you that you wanted to play your best tennis in front of an audience, but you actually played way worse than you usually do?

Maybe you played very defensively because you didn’t want to make foolish mistakes in front of your parents.

Or you wanted to impress an agent who was watching just a few games.

You want to get into that academy he mentioned, so you modify your game and try to hit incredible winners from every angle of the court.

As a young tennis player, you want to impress your parents and potential sponsors, because you know your career depends on them.

You depend on feedback from many different people!

So you do everything you can to play your best and win your matches when important individuals watch you.

Unfortunately, in tennis, you can’t control if you win a point or even a match.

For example, you might face an older, stronger and more experienced player than you.

So you will experience moments in which you are with your back against the wall.

In those situations, having to worry how to impress a scout, or how to cope with upset parents, can trigger a ton of thoughts:

You might have conversations inside your head, that sound like this:

OK, I should avoid making mistakes because this is what my mom told me before the match.

But wait, my coach said to play aggressive and come to the net whenever I can, even if I still don’t feel that comfortable with my volleys.

Ugh, what should I do?

Oh, and that’s the Nike guy who needs to see how good I am, so don’t do a double fault right now, whatever happens…

And boom- you hit a double fault.

Now you feel embarrassed and start getting even more nervous.

The irony is that tennis depends on taking risks and having courage in key moments of big matches.

And this is only possible once you stop fearing what others think, and instead start caring about what you want.

Before I show you how you can do this, I want you to understand that at least for kids, it is normal to want to please the most important people in your life, like your parents or your teachers.

After all, they pay for your practices and often are the ones who inspired you to pick up a racket in the first place.

Kids depend on feedback because they need guidance from adults.

At the same time, it is also important to realize that we grow older and develop our own preferences, we hit a glass ceiling and start losing matches that we should win because of the pressure we face.

For example, maybe you start panicking when matches got close because you fear that your coach will be upset and leave you for a better player.

Or you played too defensive in important matches because you didn’t want your parents to preach to you about all the unforced errors you made and that they no longer want to finance your tennis career.

When this happens, you must realize that the time has come in which your moods and feelings of worthiness and competence can not depend any longer on the validation of the people around you.

Sure- you still need feedback to improve as a tennis player.

However, as long as you fear that with every mistake you make, you might lose the support from a sponsor, disappoint your parents or get ridiculed by friends who are watching you, it will have the paralysing effect that will prevent you from proving your match performance.

This is why you must develop the kind of feedback loop that will help you win more matches in a very short time.

Let me give you two ways how you can start this process immediately:

Mental Drill #1: The Independent Feedback Loop

To become a better tennis player, you need to set yourself learning goals.

For example, you might choose to work on your serve or your backhand.

Or on your speed and movement.

Or on your match tactics.

At the same time, you also want to measure your progress, so it makes sense to set yourself tangible goals:

For example, you might want to finish the year inside the top 100 of the ITF juniors ranking.

Or you want to win your first tournament.

But the purpose of these goals is not to determine if you are a winner or a loser and satisfy the expectations of your parents and sponsors.

Instead, they serve you and your team as benchmarks that tell you if you are improving your game and moving forward in your career, or if you need to make adjustments in the way you train.

I call this the Independent Feedback Loop because you choose your own growth goals which are independent from third party expectations, and then you set yourself benchmarks that help you track your progress, without caring too much whether you win or whether you lose.

To introduce the Independent Feedback Loop, try this:

Sit down with your coach, and set yourself a training plan for the next month that is dedicated to improving one specific area of your game.

This could be mean improving a technical skill, introducing new match strategies or working on physical aspects of your game, as your fitness.

Next, set yourself a measurable goal- but make sure it serves purely to measure your progress.

This means you and your team have to learn how to stop caring too much about specific results and more about whether you are improving your "learning goal", or what you need to do to enhance your practice regimes.

Mental Drill #2: The Detached Feedback Loop

For example, after making a stupid mistake you might tell yourself:

I’m such a loser!

There is no way I can win if I play like this!

I hate myself for messing this up again!

To silence those self-judging voices, you need to avoid self-evaluating yourself once you step onto a match court, by developing what I call the detached feedback loop.

The detached feedback loop is a state in which you focus on giving our best because you feel detached from any need to prove yourself with specific results.

Instead, you set yourself match goals that are fully within your control, like for example your attitude and your on-court behavior.

The reason you can afford not to care about results is because you know you have been working hard on the practice court, and that worrying about outcomes will not help you.

Sure, fear of losing will still show up from time to time- after all, you are a human!

However, you will now be able to face your fear with the courage that lets you play your best game and enjoy the competitive nature of tennis without correlating your mood to specific results or feedback from others.

As a result, you no longer worry about what your parents will say, or what a sponsor will think if you do not perform as they expect.

So how can you access the detached feedback loop?

Let me share with you three simple steps:

Again, sit down with your coach and team, and strike a deal:

For the next month, have them measure only one criteria during your matches, your attitude.

One way to do this is by asking them to rate your match performance from 1-10, based on one of these criteria:

- How well was I fighting during the match?

- How was my attitude after winning points?

- How was my attitude after losing points?

The goal is that you are no longer being judged for your results, but instead, for something you can control.

Next, discuss one specific action step you can do to increase your rating by at least one mark.

For example, maybe you need to cheer yourself on after winning a great point.

Or you need to stop cursing yourself.

Whatever it is, try to implement that recommendation next time you play.

Finally, train yourself to feel detached from any self-judgment during the match.

This means that whether you hit a double fault or make an unforced error, you make an effort to avoid criticizing yourself.

When you do hear a limiting voice creep up, you tell yourself:

Stop!

Then you replace the self-judgment and get yourself back into the moment by telling yourself something like this:

Let's focus on getting ready for the next point and giving our best.

It’s that simple, but it does take some practice.

So please give it a try.

If you want to learn more mental drills and dramatically improve your mental toughness, I recommend you read my Ultimate Guide to becoming a Mentally Tougher Tennis Player.

In this Guide you will learn:

- 13 mental toughness drills that will give you the confidence to fight hard and give your best regardless of the score.

- How to constantly improve your game, love the thrill of competition and become a world-class player by practicing less not more!

- What you need to do in those pressure-filled moments that make feel so tense you can barely hold your racket!

You can download the Guide below.

Get your free PDF copy of my 25,430 words long epic Ultimate Guide To Becoming A Mentally Tough Tennis Player!